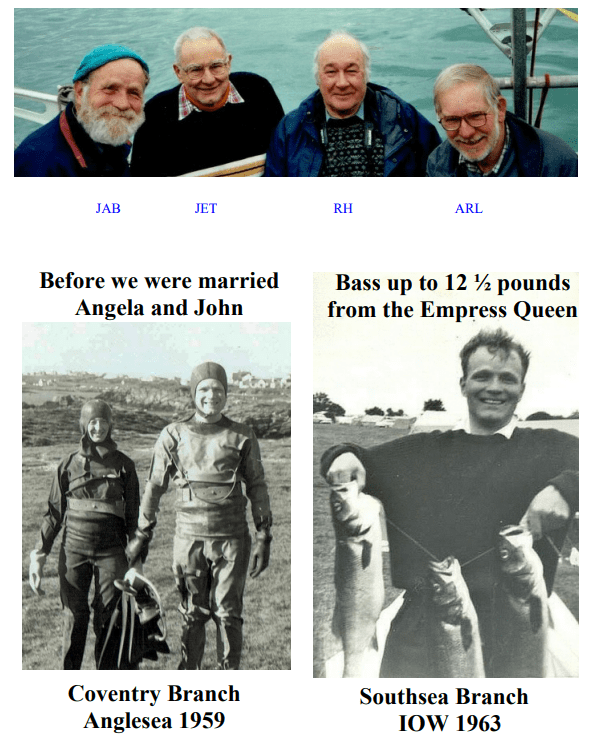

Retired diver turned poet remembers uncovering Henry VIII’s warship the Mary Rose, “it was never really lost, only relocated”. John Baldry recalls his diving career from the start, to hanging up his fins, through a collection of poems titled the ‘Diving Ditties’. By Leonora Ellis

John Baldry is 91 now and unable to dive with the weight of modern equipment. I say modern because he started diving with a mask which, he writes, had “two snorkels, one each side with ping pong ball valves to seal the tube before you swallowed any water.” Unable to leave his home, I initially emailed John, and didn’t hear from him for just over a week.

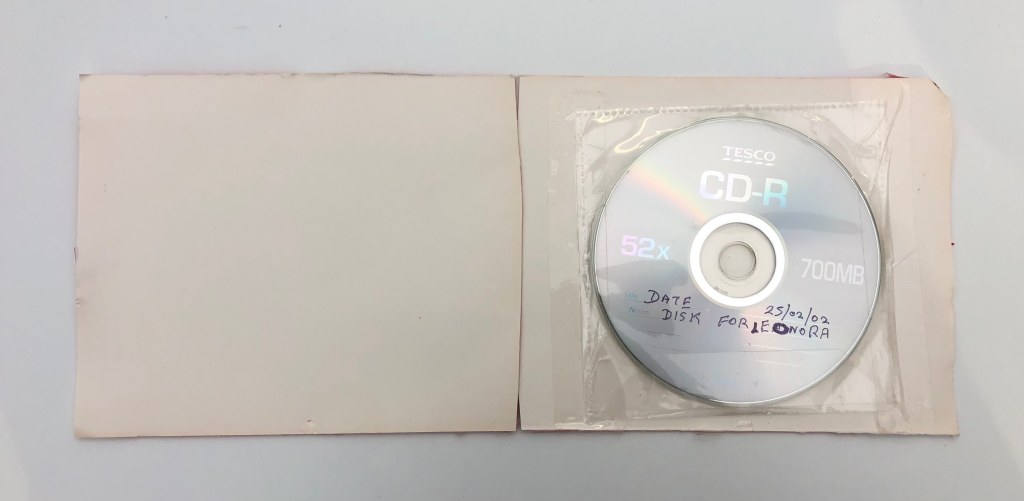

A few days later I received a letter in the post. His answers were enveloped in a bright red wonky edged cardboard pouch. Around the outside, a small paper slip titled, ‘Notes for Elanor’. John had dug out every scrap of information relating to his long history of diving and put it all on a disc for me (‘DATE 25/02/02 DISK FOR LEONORA’). It felt like a piece of treasure. I waited for a friend to transfer the contents to me. It was all very exciting.

Over his diving career, including the discovery of the Mary Rose warship, John had written lots of little poems chronicling special moments out at sea. He put them on a CD, letting me into a rich lifetime of memories. Tales that might have been left far behind, were now uncovered on a PDF: odes upon odes upon odes, ‘Diving Ditties’, unfinished odes, ‘other odes’, ‘Potty Purge’. Initially, I thought I was looking for a story on the Mary Rose, one of Henry VIII’s battle ships which survived two wars and for most of the King’s reign. In 1982 she was lifted from the depths of the English Channel where she sank during the Battle of the Solent, viewed by around 60 million people on live television. She is the only salvaged ship of her kind in the world, and with it came an abundance of new information about the lives of the crew.

The mission to uncover the ship was largely down to Alexander McKee, who initiated ‘Project Solent Ships’ in 1965.

The official Mary Rose website credits the discovery of the ship to McKee with whom John worked closely, going out in boats along with Professor Eggerton. “John [Towse] and I were positioning our boat over the wreck and when satisfied dropped a large red marker buoy over the spot securely anchored with a heavy weight. A frustrated McKee and Eggerton came over to our buoy and immediately recorded the now famous ‘W’ feature … The W feature was made by the Mary Rose lying on its side with all above the mud eroded away. The W was made up by the two sides of the hull and a portion of a central deck. Eggerton’s recording is now displayed In the Mary Rose Museum.”

I suspect John is overly modest to his part in the raising of the Mary Rose. “To be honest I am a little embarrassed about being given this certificate which hangs in my bedroom, when I did so little, and others did so much.” McKee’s voice was often the one most heard; one of the recognisable personalities attached to the war ship. John, however, doesn’t fully subscribe to the “lost” ship narrative, “the Mary Rose was never really lost, only relocated” he writes.

John fondly recounts the dive that launched his desire to make a hobby of descending into the depths. Cast your minds back to the epic 1955 war film ‘The Dam Busters’, located on the Möhne Reservoir, a large man-made glassy expanse. On googling it I was reminded of Argal Reservoir, which is not far from Falmouth where I am writing from. Both are beautiful stretches of water, nestled into a basin.

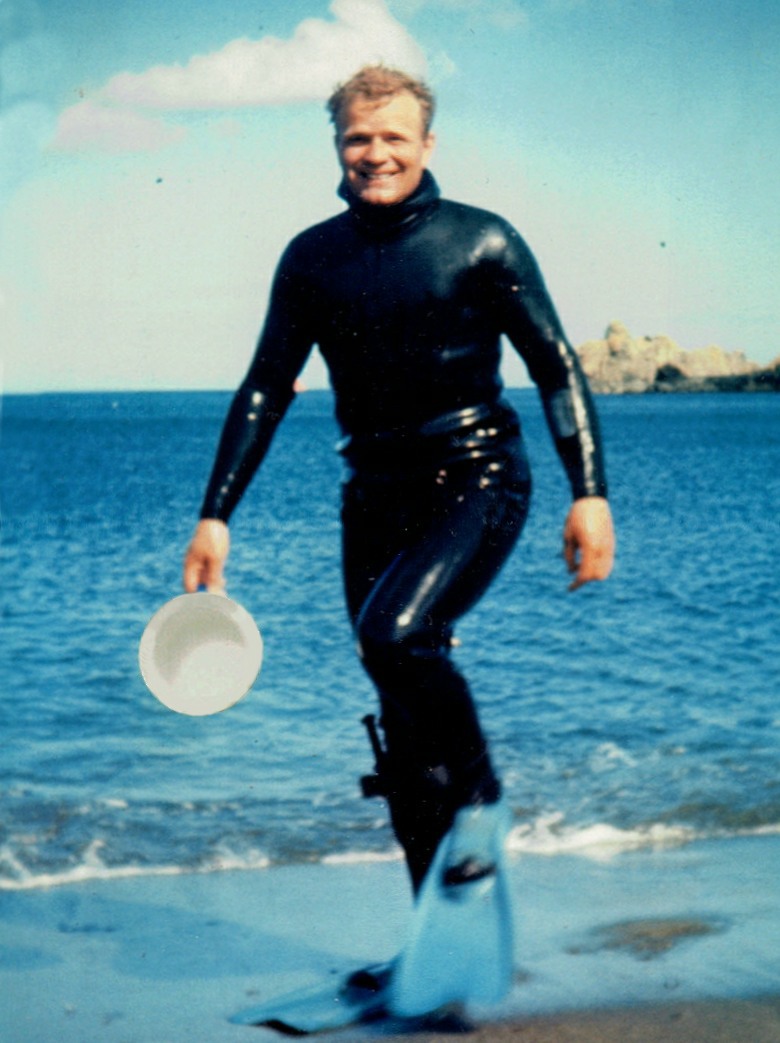

John was doing his National Service in the REME in Minden Germany, and during a short leave he had the opportunity to dive to the bottom of the reservoir. “Although there were only boulders covered with green slime, there were also small fish and a few eels about. I was hooked”.

And his coldest dive? I ask. That was in the Big Freeze of ’63. John sent me a poem of seven stanzas and four lines called ‘My Coldest Dive’. He writes about how he was unsure why they decided to dive that day, the sea in early 1963 was extremely cold reaching +8C at daytime. “Portland Harbour was the site…We crunched out over the frozen beach”. John is a beautiful wordsmith, describing the snowflakes which sunk to the seabed making “the mud below peppered white”. He and his comrades were baffled by the experience, in what world do snowflakes sink through sea water only to melt at the bottom of the ocean? He says that he still feels a sense of disbelief when relating the tale, “sinking snowflakes, they shook their heads”.

Another ode, ‘Shark’, it is audaciously titled. John was diving ten miles out from France when he and his crew spotted a “monster” in the glistening water that summer’s day. In a mere 9 metre fishing boat, the ocean dweller was at over half their boat length so couldn’t have been a Basking shark or a Porbeagle says John. “Was it a Great White that [they] had seen that day?” John still remembers its beady eye on him, they both watched, calculating each other’s next move.

I read on captivated by his storytelling: ‘Freddy the Fearless Flatfish’, ‘Despicable Catch’, ‘Scalloping on the Lulworth Banks’, ‘Hanging up my Fins’. There are around 22 odes to uncover. I am perhaps most astonished by ‘The Tusk’, for it seems absurd that John discovered ivory from a 60,000 years extinct straight tusked elephant “possibly transported in an ice sheet, from an Ice Age in retreat”. A diver’s life hey.

His words seem to list all the reasons why divers stay that two or three minutes extra under the surface, even if their bodies are telling them to retreat to dry land. With only yourself to trust, diving is a unique sport, you must be constantly in control whether one day you are confronted by an elephant tusk or the next a shipwreck. For many, swimming in the sea makes our mind turn to what might be below us, deep sea monsters and creepy crawlies on the ocean bed. For divers this becomes reality as they submerge and fall deeper and deeper. Unknown creatures dominate some of the deepest parts of the ocean, and divers are some of the only people that can interact with this world.

In retirement John kept on with his sailing and diving for as long as he could. “At 65 I was getting too old to dive alone but that’s what we did then” says John, “the boat cover might have been pulling up a dead diver”. Other than sharks and other deep-sea creatures, another serious concern for divers is Rapture of the deep (Nitrogen Narcosis), “tolerance to narcosis seemed much less” John cheerily rhymes in ode 22 ‘Hanging up my Fins’. Indeed, as divers grow older the anatomy no longer stands up quite as efficiently to the physical demands of diving.

John’s Epilogue:

Epilogue

Before I finally close my eyes,

my diving history I’ll summarise.

I never dived the Seven Seas

with work and family to appease.

Around me many hairy divers,

were natural born survivors,

they could drink until the dawn

when with heaving gut I had withdrawn.

That’s how for me the scene was set,

for easy simple dives and yet,

in retrospect it was not bad,

these odes have told the fun I had.

I can with terminal honesty confess,

diving etiquette we did transgress. But war graves were forbidden spots

as were lobsters in still marked pots.